Archaeologists and historians from Australian National University, the University of Western Australia and the University of Canberra recently teamed up with a group of First Nations Australian cultural historians to undertake a unique expedition recording ancient art carved into boab trees. Their goal was to find and document the existence of artwork carved into the surface of boab trees in the arid Tanami Desert of northwest Australia, a rarely visited section of the vast continent. The ancient artists were the ancestors of today’s First Nations people. There was a sense of urgency to this mission, since many of the most ancient boab trees in this region could be nearing the end of their long lives.

“Unlike most Australian trees, the inner wood of boabs is soft and fibrous and when the trees die, they just collapse,” explained Australian National University archaeologist Sue O’Connor, the lead author of a report on the expedition published by Antiquity. “Sadly, after lasting centuries if not millennia, this incredible artwork, which is equally as significant as the rock art Indigenous Australians are famous for, is now in danger of being lost.”

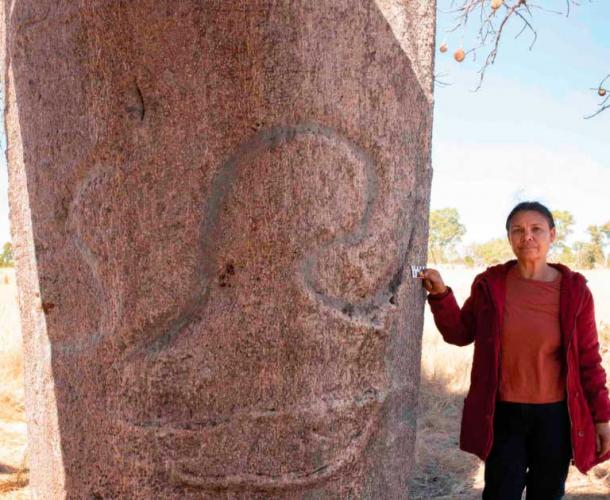

Fortunately, the boab tree artwork expedition was a success. During a far-ranging search, the team found a dozen boab trees that featured this unique type or artwork, which appears to include images of the King Brown Snake, a mythological version of a real snake that is common in western Australia.

First Nations member and expedition participant Brenda Garstone highlighted how important it was to preserve and protect indigenous artwork and the stories it tells, so traditional wisdom will not be inaccessible to younger generations. “We are in a race against time to document this invaluable cultural heritage,” explained Garstone.

Hunting for Boab Tree Carvings in the Tanami Desert

Fieldwork on this project of discovery began in June 2021. To prepare for their search, the archaeologists marked off an area of approximately 62 square miles (160 sq. km) in a treeless and sun-dried region that borders western Australia on one side and the remote Northern Territory on the other.

The team entered this foreboding desert zone seeking to take high-resolution photographs of every boab tree they could find. They paid special attention to those that might feature ancient carvings known as dendroglyphs.

Previous explorations in the 1990s had indicated the presence of such trees in the Tanami Desert. At the time, not all of these trees were photographed, however, and their exact location was not written down. The new research project sought to verify these old sightings, while creating a more detailed visual record and a map of the still-existing boab trees and their dendroglyphs.

Over the course of this extensive survey, the researchers found 12 boab trees that included carvings of distinguishable pictographs. The most common image to appear in these carvings was that of snakes, followed in frequency by drawings of emu and kangaroo tracks.

Some of the snake images were coiled while others were extended, portraying movement. Abstract geometric shapes were also present in the collection of images, as were images of what may have been meant to portray gods in animal form.

a) Enlargement of a snake carving, showing areas of damage to bark caused by insect larvae; b) location of carving on boab tree shown in a); c) partially collapsed boab, with elaborate snake carvings on the trunk and low branches; and d) Darrell Lewis sitting next to a low branch with deeply carved snakes. (Photographs a–c by S. O’Connor; d) by D. Lewis / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

Using Boab Trees as a Storyboard

Taken as a whole, the dendroglyphs tell the story of the mythical King Brown Snake and its travels through the Tanami Desert region. Its path would have been considered sacred, and may have been followed by First Nations hunter-gatherers seeking to survive in a harsh landscape.

While the First Nations members of the research team are familiar with the mythological traditions of their people, even they have no way to tell for sure when the images were carved. “They [boab trees] are often said to live for up to 2,000 years but this is based on the ages obtained from some of the massive baobab trees in South Africa which are a different species,” said Professor O’Connor said.

“We simply don’t know how old the Australian boabs are,” stressed O’Connor. Without that knowledge, she confirmed that would be impossible to precisely date the dendroglyphs to an exact time in history. This is a problem they hope to eventually solve. “It is vital we obtain some direct ages for these remarkable Australian trees, which help tell the story of First Nations Australians and are the source of a rich cultural heritage.”

a) Open-mouthed snake and emu track (right), northern Tanami Desert. The boab tree carving is approximately 1.2m across; b) boab tree with coiled and extended snake carvings, northern Tanami Desert (D. Lewis/ Antiquity Publications Ltd ).

Source: ancient-origins.net