In the year 185 A.D. Chinese astronomers witnessed a temporary ‘guest star’ emerge in the sky.

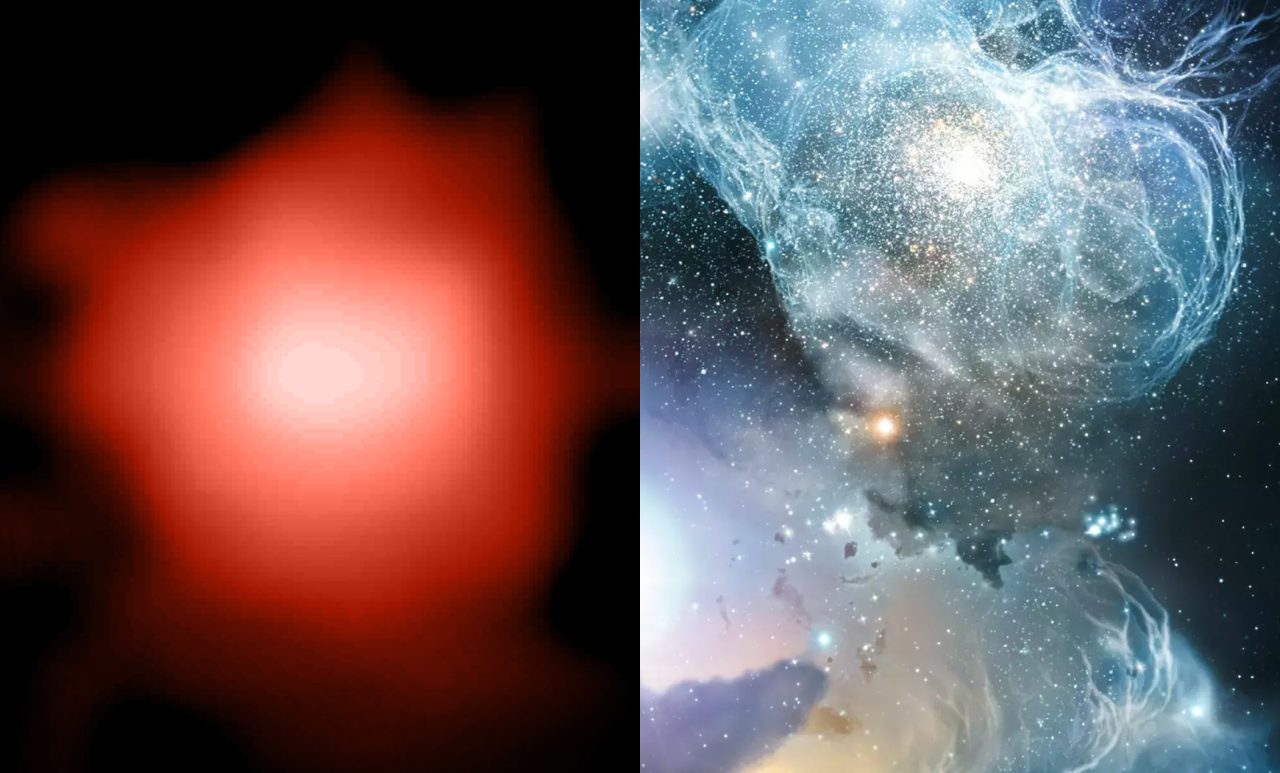

Incomparable detail has been unveiled in the remains of an ancient supernova explosion in a new image captured by a camera made specifically for studying dark matter.

The picture was taken by the Dark Energy Camera on the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Victor M. Blanco 13.2-foot (4-meter) Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. It reveals tendril-like clouds of dust and gas spreading around the supernova’s center.

Between the constellations Circinus and Centaurus in the southern sky, these torn pieces encircle a region that is bigger than the apparent size of the full moon. The strange cloud, also known as object RCW 86 to astronomers, is thought to be the remnants of a star that exploded with such ferocity more than 1,800 years ago that it caught the notice of ancient Chinese astronomers and chroniclers.

Dubbed the “quest star” by the ancient Chinese for its temporary nature, the supernova, today officially known as SN 185, was spotted in the year 185 A.D. (hence the name) and faded over eight months. Astronomers now know that the event occurred 8,000 light-years away in the direction where the sun’s closest stellar sibling, the triple star Alpha Centauri, is located.

Thanks to its ability to see a large portion of the sky at the same time without compromising on the level of detail, the Dark Energy Camera provided astronomers with a “rare view of the entire supernova remnant as it is seen today,” the NSF NOIRLab, which released the image on Wednesday (March 1), said in a statement(opens in new tab).

Astronomers hope that this new and deeper look at the object will help them better uncover the perplexing physics that drove the long-ago explosion that created it.

While astronomers today agree that RCW 86 is a residue of the SN 185 supernova, it hasn’t always been the case. For a long time scientists thought that the size of the shell was too large to have been produced in that explosion.

Calculations from previous studies estimated that it would take 10,000 years for material to disperse so far away from the dead star. In 2006, however, astronomers found evidence that the shell developed at a much faster rate than they had originally believed. Eventually, observations by N.A.S.A’s Spitzer Space Telescope revealed large amounts of iron in the material, which led astronomers to conclude that the explosion that produced RCW 86 must have been the most energetic known type of a supernova, one that occurs when a white dwarf star, a dense remnant of sun-like star, consumes an orbiting companion.

These types of supernovas, known as Type Ia supernova, produce so much light that the phenomenon wouldn’t go unnoticed even in the distant past when astronomers were limited to naked eye observations.

“These supernovae are the brightest of all and no doubt SN 185 would have awed observers while it shone brightly in the night sky,” researchers wrote in the statement.

Soucre: www.space.com