‘The Chetniks killed my dear grandpa. I loved him so much. Everyone cried, and I just couldn’t understand that he was no more…’

Luka Modric is sitting in the shade. He has been told he does not have to report back for pre-season training with Real Madrid until August 30 so he and his wife, Vanja, and their three children have come to his home outside Zadar on the Dalmatian coast.

His house is filled with happiness and laughter but now and again he thinks back to his own childhood and what happened here, and in the mountains 25 miles away, and he looks out to sea.

‘Sometimes, when I go to the centre of the city or pass the beaches or the areas where I used to play football and hang out with my friends, it brings back great memories,’ Modric says.

‘They were difficult times in lots of ways and I went through so many things but in general, despite everything that happened and the scars on my family, I remember my childhood as a happy childhood. I like to try to remember positive things. I have always been like this. It is easier, I think.’

It is easier. It is easier because the alternative is to dwell on the tragedy that befell him and his family on the morning of December 18, 1991 at the start of the Croatian War of Independence and which he accepts helped to shape his character and career. It is easier because there is something incredibly touching about the relationship the six-year-old Modric had formed with his grandfather and something unthinkably sad about the way the two of them were separated.

There has always been something vulnerable about Modric, whose Madrid side beat Barcelona to the Spanish league title this season but lost to Manchester City in the last 16 of the Champions League. It is part of his appeal. He is a beautiful player to watch, a midfielder with vision and grace, a player who can take hold of a game and control it, a player whose fragility is an illusion. Part of the joy of watching him play is that it feels like you are rooting for the underdog. He is a Goliath in the frame of a David.

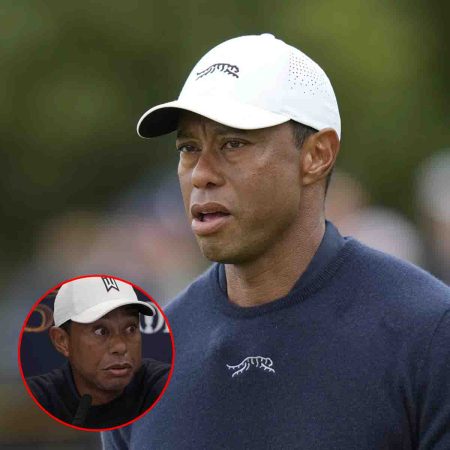

The Croatian beat both Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo to win the Ballon d’Or in 2018

He is 35 next month and one of the undisputed greats of the game, the only player in the last 12 years apart from Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi to win the Ballon d’Or, the prize given to the best player in the world. But in his youth, when he played for Dinamo Zagreb, people said his frame was too frail ever to make it in the Premier League or La Liga. He was simply too small, they said. He would be like a child fighting against men.

When he moved to Spurs, people said he would be overwhelmed by the physicality of English football. He thrived in it. In fact, he thrived so much that four years later, he was signed by Real Madrid. In the early stages of his career at the Bernabeu, he was named the worst signing in Madrid’s history. Now, seven years later, he is one of the most decorated players in the game. He has won the Champions League four times. In 2018, he led Croatia to the World Cup final.

There is steel hidden beneath that frailty and it comes from his childhood and the things he endured and the determination it bred in him that he would never give up no matter what anybody said about him. It comes from running for the underground shelter in Zadar when the sirens wailed to warn of an artillery bombardment. It comes from living as a refugee in a hotel room with his family and it comes from what happened to his grandfather.

The midfielder overcame doubters at the start of his Real Madrid career to prove himself

He has never talked about it at length before. ‘I am not comfortable in the spotlight,’ Modric says. ‘I was always a bit of a closed person. I am not a fan of giving interviews. Only if I have to. There is not any special reason for that. I don’t have anything against journalists. It is just that I am like that as a person. I don’t like to be in the spotlight or to talk much. I like to keep my circle close.’

But now, as he sits staring out at the sea, Modric talks about his Grandpa Luka and the bond the little boy shared with the old man. It started when Modric was named after him. ‘I was very emotionally connected with my grandfather,’ he says. ‘I was always with him. My father gave me his name. It was not easy what happened but when you are young, you do not understand these things. He is not with us any more and nothing can get him back.’

Modric was his grandpa’s first grandson and the family was astonished at how soft and gentle he was with the boy. Grandpa Luka was a street mender who looked after the old road between the coast and the mountains of Croatia. He was a rugged, handsome man and Modric says that today we would call him ‘a tough guy’. He kept a herd of 150 or so goats and sheep and Modric would help him take them to the mountain pastures.

Sometimes, Grandpa Luka would take the young boy out hunting rabbits. He let him hold his shotgun once and there is a picture of them together in Modric’s enthralling new autobiography, the young boy beaming with pride. Instead of going to nursery school, Modric spent his weekdays at his grandparents’ old stone house while his parents worked at a clothes factory a few miles away.

‘I felt his love in his kind-hearted reactions to my mischief,’ Modric writes in his autobiography, ‘or when he took me to my bed and stayed there until I fell asleep. I felt his kindness and his warmth; the patience with which he passed his knowledge on to me. I couldn’t wait to go back to him, to the stone house under the Velebit mountains, my eagerness expressing our special bond.

‘As soon as I was big enough to walk around on my own, he took me with him wherever he went. Whether shovelling snow, stacking hay, taking the cattle to pasture, going to buy building materials, carrying out all kinds of repairs, as well as a whole line of other things that needed to be done around the house, my grandfather always treated me as his assistant.’

But at the start of the 1990s, the old Yugoslavia was breaking up, Croatia had declared independence and war was coming. Serbs had begun to take control of the mountainous area where Modric’s grandfather lived and the atmosphere grew tense and dangerous.

Most of the residents left but Modric’s grandparents stayed. There were intermittent reports of bands of Chetniks, Serbian nationalist thugs, roaming the mountain roads, and one day Modric’s grandmother phoned to say she had seen Serb army trucks on the road and that her husband had not returned from the pasture.

A contemporaneous report said that a group of Chetniks had set out along the winding mountain roads earlier that morning, singing nationalist songs as they drove through the countryside. They came across Modric’s Grandpa Luka as he was leading the flock of sheep and goats into the pasture and ran at him, screaming and shouting, filled with blood-lust.

‘Who are you, what are you doing here? This is Serbian land,’ the report says they yelled at him. Then they mowed him down with a machine gun at close range. They left him there and drove on to continue their rampage. They killed six other innocent men that day. None of the murderers was ever brought to justice. Modric’s father found his own father’s lifeless body and brought him home.

A young Modric pictured going hunting for rabbits with his grandad, who was tragically killed

‘I didn’t know what had happened when they brought him to our house,’ Modric recalls in his autobiography. ‘The only thing I felt was grief. My father put his arm around me and took me to the coffin. He said, “Son, go say goodbye to your grandpa”. I wasn’t able to grasp that was the last time I would ever see him. My parents led me out of the room — they wanted to distance me from the tragedy. My heart breaks every time I think of him dying, literally on his doorstep.’

A few years later, when Modric was 10, his teacher asked his class to write about something that had made them sad or scared. It was the first time he had articulated his grief.

‘Even though I’m still little,’ Modric wrote then, ‘I have experienced a lot of fear in my life. The fear of war and shelling is something I’m slowly putting behind me.

‘The event and the feeling of fear I will never forget took place four years ago when the Chetniks killed my grandfather. I loved him so much. Everyone cried, and I just couldn’t understand that my dear grandpa was no more. I used to ask if those who did this, and who made us run away from our home, can even be called people?’

Modric mentions the letter and looks out at the shimmering waters of the Adriatic again. No one was ever brought to justice for the murder of his grandfather and I ask him whether he still harbours bitterness or hate towards Serbia and its people. But Modric is a gentle, modest, unassuming man with a ready smile. He is easy to like and when I mention bitterness and hate, he shakes his head.

‘No hate,’ he says. ‘Sometimes tragic things happen. I have no hate towards anyone. What happened happened. You cannot forget what happened but no hate. My family has found peace eventually. We don’t know who did it. There are people who take care of these things and they need to take care of that and make justice. There are people who judge what happened in the past but we are at peace with knowing he is not with us.’

Modric has carried his grandfather’s memory with him throughout all the triumphs that have marked his career. When he won the Ballon d’Or in 2018, he was there with him. When he achieved the greatest triumph of his club career, winning La Decima, Real Madrid’s 10th European Cup in 2014, he was there. When he led Croatia to the World Cup final in Russia, he was there.

Maybe without what happened, Modric would not have made it. Maybe the steel in his soul would not have been so strong. Maybe his spirit would not have been quite so unbreakable. Maybe, if it were not for the privations of war, he would not have fought so ferociously to make it in the game when rejection and doubt followed him around like faithful but unwanted companions.

‘All the things that happened in my childhood helped me to become more tough, to believe in myself and to fight for my dreams,’ Modric says. ‘I never gave up and every doubt for me was extra motivation to prove people wrong or prove I can do something. When I was doing something I did well, it gave me even more confidence or strength for the next challenge. That was important for me not to give up.

Modric’s autobiography is out on Thursday, August 20, and is available to pre-order now

‘I say that to young kids: never stop believing in yourself, not even when people tell you that you cannot do this or this. It is the only way you can succeed in something, not just in sport, but in general. You have to believe in yourself, taking motivation from things people are saying. That helped me never to give up. I am a fighter in general and it never crossed my mind to give up because someone said something.

‘My grandfather was killed and I have been through a lot of things in my childhood but when you go through what I went through as a kid, it helps you put things in perspective and you don’t stress yourself all the time. You accept that every defeat, or every obstacle, is part of football and you learn to live with it.

‘It affects you a lot. It left big scars on my family, especially on my father. It was a traumatic time. It was not easy but my parents were trying, for me and my sister, to keep us apart from all the worries so that we did not feel too much what was happening around us. It helped us to be even more together and it shaped my character and made me grow up as a person, to fight for myself, to be modest, to stay always with both feet on the ground and these kinds of things.

‘I thought of my grandfather every time I won anything. I always remembered him. I would like him to see all the things I achieved. I would like to have him here with us but I am sure he is watching me from above and he is happy what I became and what I achieved.’