The number 10 has become an elusive creature, one perilously close to extinction. Where is our next star playmaker coming from?

Modern football doesn’t seem to have the shape or structure for a player who can change a game. Those who found time to stop, to take that crucial half-beat when under pressure. Zidane, Laudrup, Platini and Bergkamp all took that extra half-second to out-think an opponent before laying off the killer pass.

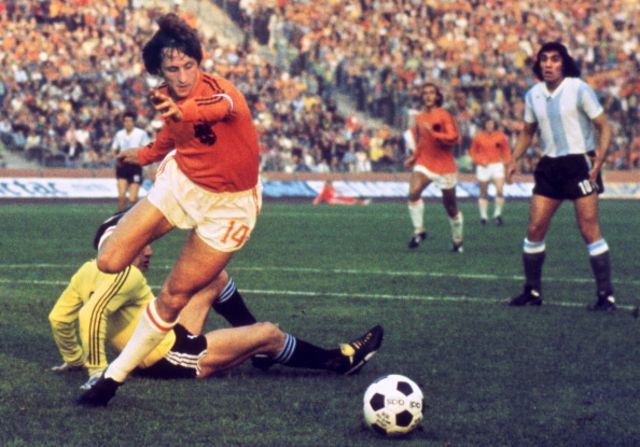

The EPL now seems tied to the Cruyff/Guardiola/Klopp/Arteta/Ten Hag seam, the fast-moving high press. Where do the thinkers get time to evaluate the shape of a game? Could it be a cultural thing? The vast amounts of money swirling around? The conveyor belt of managers replaced every two weeks? For the number 10 to survive we need stability; we need safe environments where players are allowed to shine.

The game has morphed into something which expects full-backs to become wingers and overlap opponents and the closest we have now would be the false 9, like Messi at his peak at Barça when he was allowed to cut back into midfield when the side was in possession.

Of course, keen scholars of the game know this is hardly a new thing. It was made famous by the great Hungarian side coached by Gusztáv Sebes, the Mighty Magyars with Ferenc Puskás and Nandor Hidegkuti. Sebes openly gives credit to the likes of Jimmy Hogan, the English coach trailblazing across Europe from 1910 who changed the focus to fitness and ball control and eventually evolved into an attacking midfielder playing behind two attackers.

Surprisingly, the number 10 was snubbed by England’s national coaches. Glenn Hoddle had to move to Monaco to be fully appreciated as a bona fide 10. Ron Greenwood and Bobby Robson considered Hoddle a luxury item. Interestingly Brian Clough was a fan, describing Hoddle’s style of play in the bruised and mud-soaked killing fields of this era as someone who played with moral courage. It would take Arsene Wenger to encourage him to unleash the passes, set-pieces and glorious goals by playing his natural game.

Maradona’s nature and career were defined by his social background. That incredible talent was ring-fenced by cheek and nastiness. There were two Diegos – the loving father, brother and son and then Maradona, the player with otherworldly ability who was almost allowed, expected even, to become a flawed icon. You could not have one without the other. He grew up in abject poverty. Football was an escape.

When writing The Number 10: More than a Number, More than a Shirt and researching my favourite 18 players from various eras, a few elements came to light. One was that allied to their unbelievable skill was hard work. Platini, Zidane, Zico, Pelé, they all worked so much at their game. You would think if they were born with such natural skill they wouldn’t have to do anything. Those who did not work on their game, like Ronaldinho for example, let the standards slide as they got older.

For many, it was about practice and repetition. Players like Zico, Zidane and Platini, once training was over, practised taking free-kicks for hours. When Zidane was playing for France and as the best player in the world at Real Madrid, he shocked people by working on the basics. He would be out after training, dribbling the ball around cones, or taking free-kicks and penalties.

When Zico was a kid he famously placed his tracksuit top over the crossbar and refused to go home until he hit it from a free-kick ten times in a row. He could be there for hours. As a player and coach, he compared the technique of passing, heading and free-kicks to muscle memory, a mechanical thing, like brushing your teeth.

The great number 10s were also brave. They had a tremendous mental attitude with many having to overcome adversity or tragedy. Despite their wonderful skill, this hunger and desire made them capable of fighting when it got tough. They could drag their side to greatness by delivering in the critical moments of a major game.

Maradona drove Argentina to the World Cup and won Serie A twice with Napoli (currently thriving but then more like Aston Villa or Brighton). Take Messi in the World Cup in December 2022 with Argentina. He knew he was playing a game that would define his wonderful career – how many times did he hear ‘Well Pelé and Maradona won the World Cup but Messi hasn’t?’ He was also shouldering the burden of great expectation from his country. Messi delivered.

Pelé’s dad Dondinho was a professional player who was badly injured. He and former Brazil star Waldemar de Brito coached him. Every aspect of Pelé’s game, from running properly with the ball, dribbling with the left and right foot, how to leap high and head the ball correctly to chesting, volleying and overhead kicks were all taught to him. Both the technical and mental side, sportsmanship, courage, honesty, self-discipline, fitness and preparation.

![]()

The wearer of the special shirt requires mental toughness and bravery, Ronaldinho watched his father have a heart attack in a swimming pool and die a few days later, Modrić’s grandfather was murdered by Serbian rebels. Roberto Baggio had real courage – he had a lifelong allergy to painkillers and played in great pain most of his career – and he was loved at every club he played for and he played for many, including the three Italian giants.

One of my personal favourites was the story of Marta. Her life from poverty to stardom began with a long three-day bus journey for a trial in Rio de Janiero and is a story of epic proportions worthy of a Hollywood movie. I included Günter Netzer because as a kid I thought he and Cruyff were just the bee’s knees. Unfortunately Cruyff was famous for wearing 14 most of his career or he would have been included too.

For the purposes of this book, they had to wear the 10 for a sustained period, and be renowned as a 10, though Cruyff is mentioned on just about every page – as he should be. We haven’t even got to mention Puskás or Eusébio here.

I think Pelé is the best ever because, like Muhammad Ali, he transcended his sport and became football’s first global superstar. When he came on the scene as a 17-year-old he changed how Brazil was perceived as a nation.

The best number 10s of all time should always encourage debate. So let’s have some fun. Who are your top three number 10s? Mine are Pelé, Maradona and Messi, in that order.