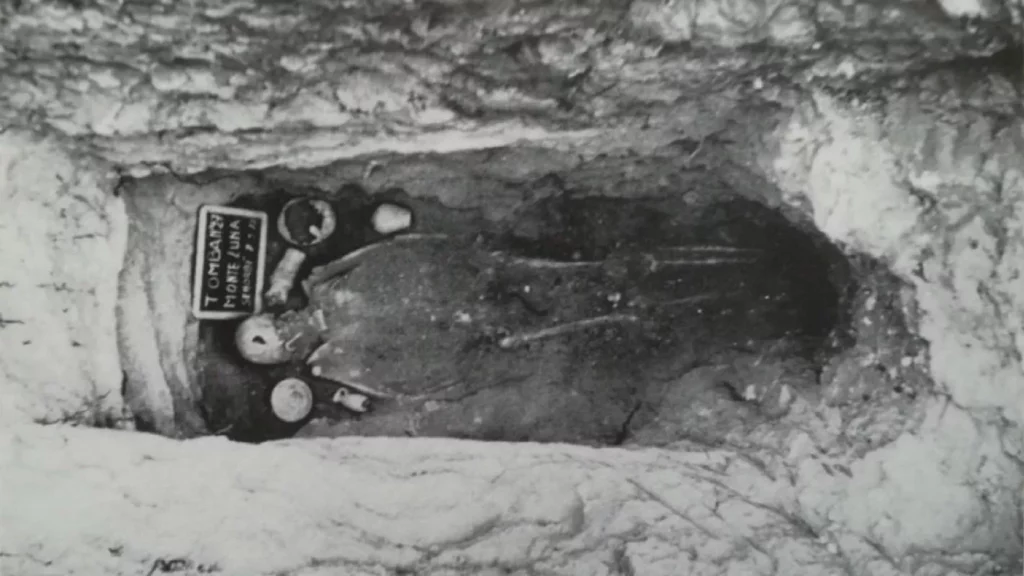

Archaeologists have dated the unusual face-down burial of the young woman at the Monte Luna necropolis in Sardinia to late in the third century B.C. or early in the second century B.C.

The strange facedown burial of a young woman, who likely had a nail driven into her skull around the time she died in Sardinia more than 2,000 years ago, could be the result of ancient beliefs about epilepsy, according to new research.

The facedown burial may indicate that the individual suffered from a disease, while an unusual nail-shaped hole in the woman’s skull may be the result of a remedy that sought to prevent epilepsy from spreading to others — a medical belief at the time, according to a study coming out in the April issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Epilepsy is now known to be a brain condition that can’t be transmitted to other people, but at the time the woman died, “The idea was that the disease that killed the person in the grave could be a problem for the entire community,” said study co-author Dario D’Orlando, an archaeologist and historian at the University of Cagliari in Sardinia.

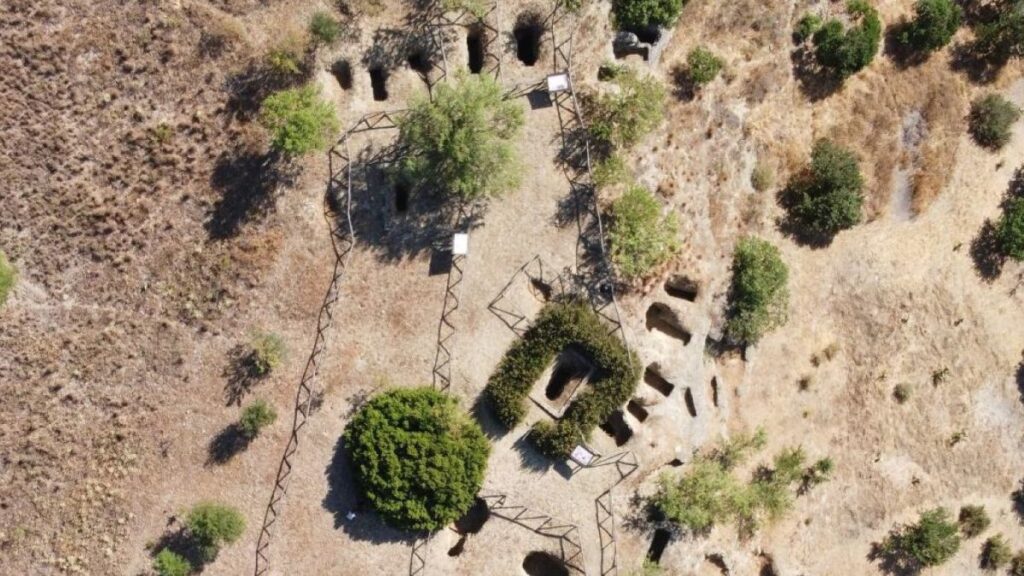

The tomb is one of more than 120 Punic tombs at the Monte Luna necropolis in southern Sardinia, which was established after the sixth century B.C. and was used until the second century B.C.

The unusual burial was found in a tomb in the Necropolis of Monte Luna, a hill located about 20 miles (30 kilometers) north of Cagliari in the southern part of Sardinia. The burial ground was first used by Punic people after the sixth century B.C. and continued in use until the second century B.C.

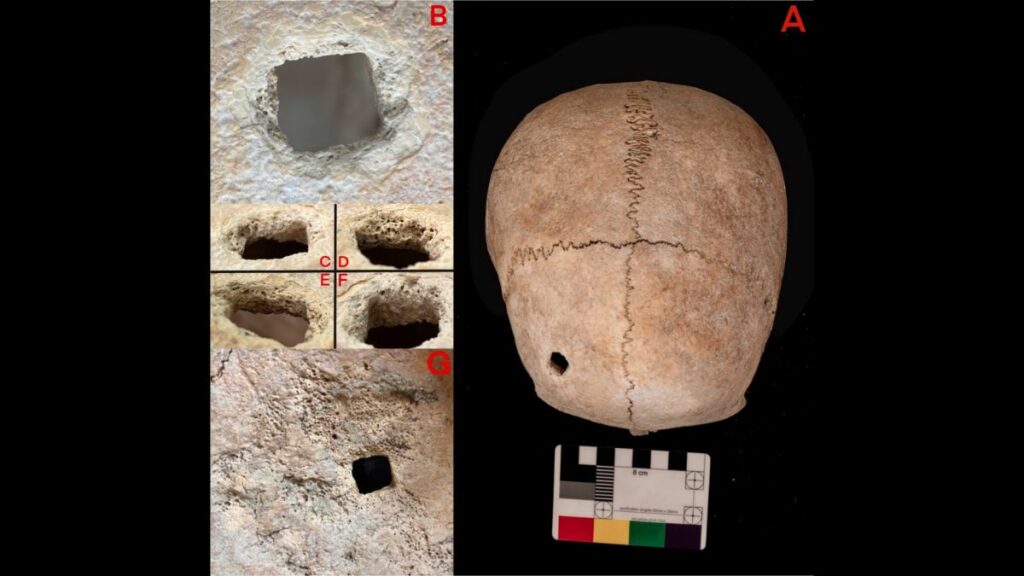

The latest study found evidence of blunt-force trauma to the woman’s head, possibly from falling, and a square hole that appears to have been made by an ancient nail.

The Monte Luna necropolis was excavated in the 1970s, and the latest study is based on photographs of the tomb and a new examination of the woman’s skeleton.

Pottery in the tomb suggests she was buried in the last decade of the third century B.C. or the first decades of the second century B.C. — a time when Sardinia, a center of Punic or Phoenician culture for hundreds of years, had come under Roman rule since the end of the First Punic War against Carthage, which took place from 264 B.C. to 241 B.C.

And a new analysis of the young woman’s skeleton — based on her pelvis, teeth and other bones — confirmed an earlier estimate that she was between 18 and 22 years old when she died.

It also showed she had suffered trauma to her skull shortly before or around the time she died. The archaeologists found evidence of two types of trauma: blunt-force trauma, which could have occurred during an accidental fall — possibly during an epileptic seizure — and a sharp-force injury in the form of a square hole in her skull consistent with an impact by an ancient Roman nail; such nails have been found at several archaeological sites in Sardinia.

The authors suggest the woman’s skull may have been pierced by an ancient nail with a square cross-section, like this one, to prevent the spread of the perceived “contagion” of epilepsy.

Medical beliefs in ancient Sardinia

Such treatment may have been based on a Greek belief that certain diseases were caused by “miasma” — bad air — that would have been known throughout the Mediterranean at that time, D’Orlando said.

The same remedy is described in the first century A.D. by the Roman general and natural historian Gaius Plinius Secundus — known as Pliny the Elder — who recommended nailing body parts after a death from epileptic seizures to prevent the spread of the condition, the authors reported.

D’Orlando suggested that this practice of nailing the skull, and perhaps the woman’s unusual facedown burial, could be explained by the introduction of new Roman ideas, which were heavily influenced by ancient Greek ideas, into rural Sardinia.

The tomb was excavated in the 1970s and the latest study is based on photographs and a new analysis of the bones it contained, in particular the young woman’s skull.

But Peter van Dommelen, an archaeologist at Brown University who wasn’t involved in the study, said the culture in Sardinia stayed resolutely Punic in spite of Roman rule.

“Culturally speaking, and particularly in rural places like here, the island remains Punic,” he said. “There’s no reason to look at the Roman world for affinities — what people were doing was entirely guided by Punic traditions.”

Van Dommelen has not heard of similar burials in Sardinia, but “it’s interesting,” he said. “It fits with a broader pattern that you can see across the world and across cultures.”

source: https://archaeology-world.com