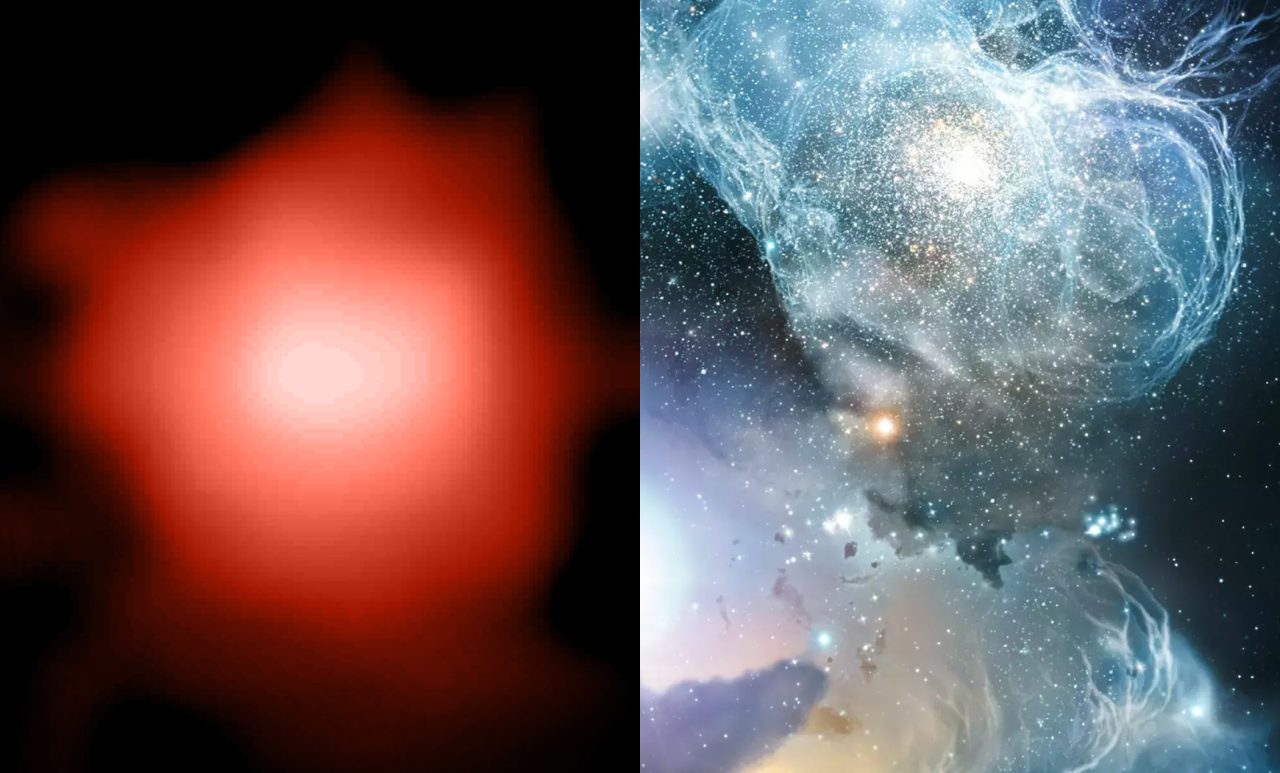

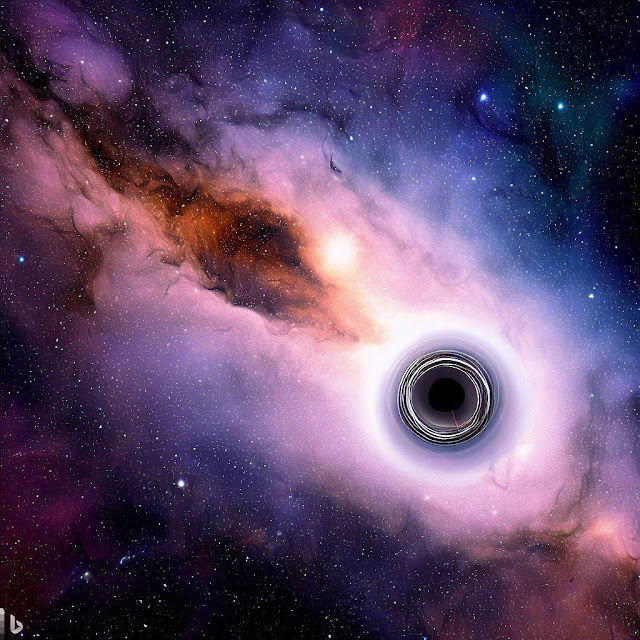

An ultramassive black hole is a black hole that has a mass of more than 10 billion times the mass of the sun. Black holes are regions of space where gravity is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape. They are usually formed when massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle.

Ultramassive black holes are rare and elusive, and their origins are unclear. Some scientists believe they were formed from the extreme merger of massive galaxies billions of years ago when the universe was still young.

How was the ultramassive black hole discovered?

A team of astronomers from Durham University in the UK and Max Planck Institute in Germany discovered the ultramassive black hole using an innovative technique combining supercomputer simulations and high-resolution images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

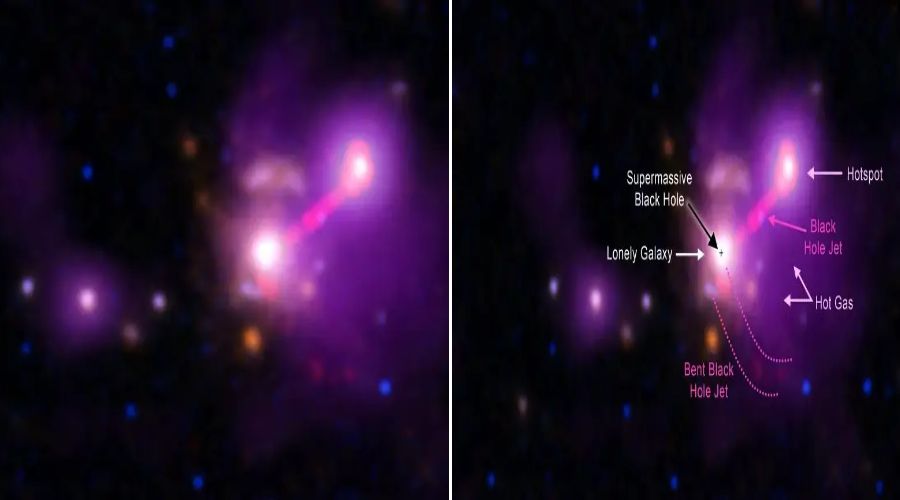

The ultramassive black hole sits at the centre of Abell 1201, a supergiant elliptical galaxy residing in a galaxy cluster of the same name, about 2.7 billion light-years from Earth.

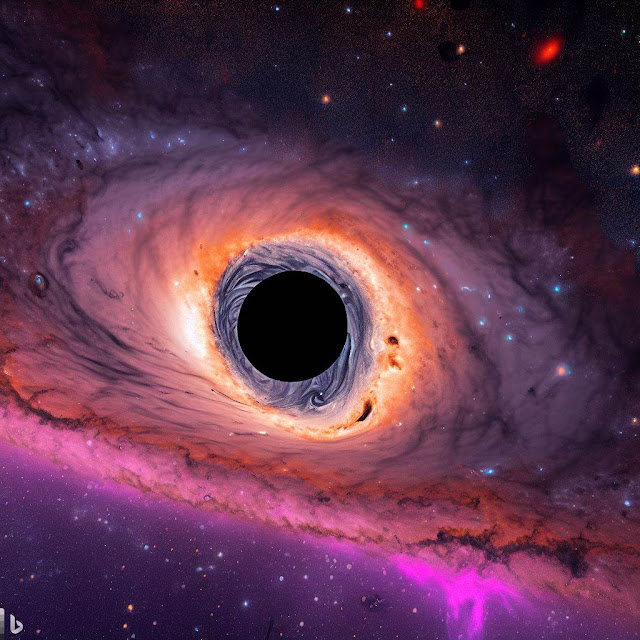

The astronomers used a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, where they took help from a nearby galaxy by converting it into a giant magnifying glass. This revealed the presence of the ultramassive black hole, as the light from another galaxy behind Abell 1201 was bending around an extremely massive object along the way.

Gravitational lensing is a consequence of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which predicts that massive objects can warp the fabric of space and time around them, and thus bend the path of light rays passing near them.

The scientists used Durham’s DiRAC COSMA8 supercomputer to run hundreds of thousands of simulations of light travelling the same path, each time with a black hole of a different mass in the way. When an ultramassive black hole roughly 33 billion times the mass of the sun was included in the simulations, they produced images that matched the real pictures taken by Hubble.

Why is this discovery important?

This discovery is important for several reasons. First, it confirms the existence of one of the biggest black holes ever detected and on the upper limit of how large scientists believe they can theoretically become.

Second, it demonstrates a new way of finding inactive black holes that do not emit any radiation or light, unlike active black holes that pull in matter and release energy in various forms.

Third, it provides new insights into how ultramassive black holes may have formed and evolved over cosmic time, and how they may influence their host galaxies and galaxy clusters.

Dr James Nightingale, the lead author of the study, said: “This particular black hole is one of the biggest ever detected and on the upper limit of how large we believe black holes can theoretically become, so it is an extremely exciting discovery.”

He added: “However, gravitational lensing makes it possible to study inactive black holes, something not currently possible in distant galaxies. This could help us understand more about how these mysterious objects form and grow over time.”

The study was published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on Wednesday 29 March 2023.